Fifty years ago, in November 1969, my sister, Sue, nearly died. She was a healthy, energetic, friends-with-many girl in her junior year at Clear Lake (Iowa) High School. I was a senior at Iowa State University in Ames. Sue, my only sibling, and I were as different as left and right. She was the extrovert—a cheerleader, homecoming queen, and the life of many parties; I was the introverted, studious valedictorian—a good athlete but never to be a BMOC. We respected and enjoyed our differences, as did our parents, Jim and Barbara.

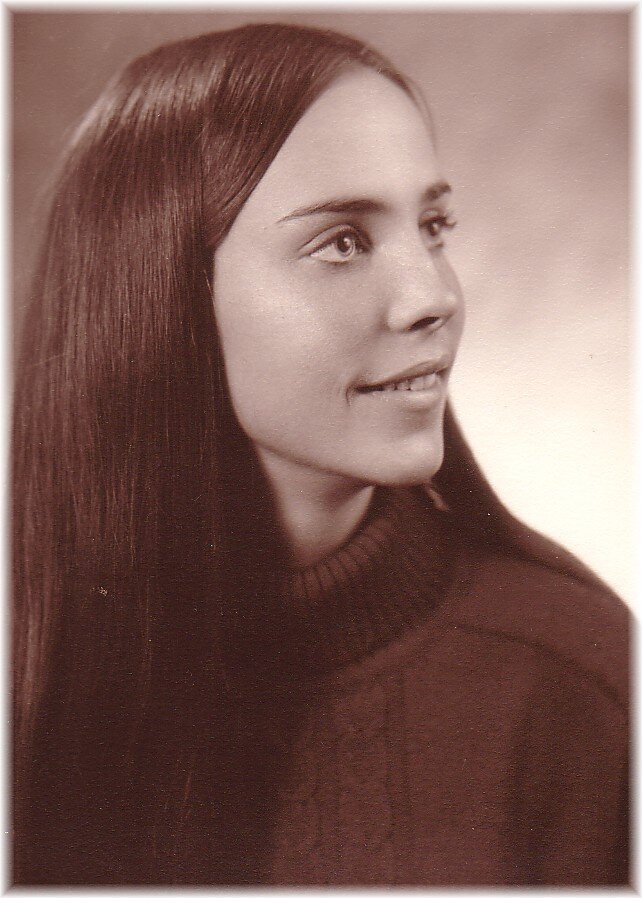

Sue’s high school graduation picture

A few minutes from midnight, the phone rang at my off-campus apartment in Ames. Our phone was on the main floor; my roommates and I lived upstairs. My landlady, Mrs. Walsh, answered and said, “It’s for you, Mike.”

“Thanks,” I said and hustled down the stairs. I never like late-night calls for fear of the bad news they tend to bring.

“Mike, this is your dad. Sue’s in the hospital.” My first thought was an accident, but Dad went on with, “She has a massive infection, and there’s a possibility that she might not live through the night.” We talked for only a few minutes before I said I would leave right away. I put on my coat and got in my car. My teeth were chattering so badly I could barely tell the gas station attendant to “fill ’er up.” As I began the 90-mile drive to Mercy Hospital in Mason City on that cold, dark November night, I couldn’t believe what was happening. I had been home three days before, and Sue was fine. I tried to prepare myself for her not being alive when I got there, but I couldn’t fathom life without her.

After I arrived at the hospital, I raced to the room where Dad and Mom were waiting and learned what had happened. Sue had come home from school with chills the night before. The next morning, she woke with a 105-degree temperature. Mom called the town doctor, who suggested Sue be taken immediately to the hospital. There she went into shock from an infection, and neither pulse nor blood pressure could be found. Her entire body turned blue; her hands and feet became ice cold. Doctors told my parents that there was a possibility of acute leukemia or a brain tumor, and she might die. Dad went to the hospital chapel and cried. Mom sat in the waiting room staring blankly into space, in shock.

That evening, doctors gave Sue a large drug dose and predicted that she would respond in two hours. At ten o’clock, her condition hadn’t changed. They said there wasn’t hope for her if she did not improve in the next few hours. At two o’clock in the morning, when I arrived, she was at death’s doorstep. Dad was the only family member allowed to check on her, and he could be in her room for only five minutes per hour. He looked so dejected each time he returned to give us his update: “There’s been no change.” Thus went the longest night of my life—my mom, dad, and me sitting forlornly on the uncomfortable waiting room chairs, looking out at the dimly lit hallway. There was an eerie silence, broken occasionally by the click of nurses’ footsteps. Each time we heard them we feared someone was bringing us news that Sue had died.

But death did not enter Sue’s door that night, proof that prayers sometimes are answered and miracles do occur. Just as we were about to give up, Dad returned with good news from his early-morning check. He thought Sue’s hands and feet had some warmth that hadn’t been there before. There were signs her kidneys had begun working, too. By noon, there was tremendous improvement. Doctors said the critical period was over and that Sue could pull through. We stayed our second night in the waiting room, but this one was much less stressful than the first. We ordered a pizza, curled up in our chairs, and slept soundly for the first time in two days. By the next evening, Sue was asking for a hairbrush, makeup, a telephone in her room, and visits from her family and friends. Within a week, she was out of the hospital, in school, and back to her former self, showing no ill effects from what had happened. Doctors did not know how and why she survived or what she had. Later, they surmised it to be toxic shock syndrome. Today, I reflect on what we would have missed—a million laughs and many memorable life experiences—had she not made it through that ordeal. Here are just a few.

She enjoys (and often seeks) the limelight and has done things I would never have the nerve to do. For example, in the 1980s when living in California, she went to The Price Is Right game show six times, yearning to be selected. Her husband and a good friend had been chosen to be contestants, but she hadn’t. One day she went alone to stand in the contestant-want-to-be line. She told the producer, “This is my seventh try. You might as well pick me because I’m going to keep coming back until you do.” The producer listened. Sue won several prizes, joked with host Bob Barker, and just missed winning $10,000 on the final spin. A few years later, she appeared on the $25,000 Pyramid game show hosted by Dick Clark. She won an all-expenses-paid trip to Rome and, with her celebrity partner Nipsey Russell, was one answer away from winning the $25,000 jackpot.

Sue being Sue

Sue has a self-deprecating sense of humor, and funny situations have a way of finding her. When she was working at a Long Beach athletic club, the club hosted a huge Halloween costume contest, and she drove to work that day wearing an Oreo cookie costume she had made consisting of a big white wig; a white leotard; a large, brown cardboard-cutout cookie; and brown puffy shoes, with “OREO” written across her forehead. Driving down busy Beach Boulevard, she heard something fall from the roof of the car. It was the change caddy she carried at work, which contained $100 in bills and coins. As she glanced in her rearview mirror, she saw bills and change flying all over and rolling down the road. She slammed on the brakes, got out of her car, and chased down as much of the money as she could. Cars honked and people pointed; the site of an Oreo cookie chasing money was pretty comical, even for California.

When living in Scottsdale, Arizona, and selling real estate, Sue was invited to appear on a much-watched television show on which Diane Hunter invited realtors to talk about their listings. She was told to report at 6:00 am for the taping. Sue noticed that Diane had a team of makeup artists and attendants around her, and when she spoke, if she made a mistake, the producer hollered “cut” and they did a retake. When Sue’s turn to be interviewed came and Diane asked her to talk about her property, Sue’s mouth was so dry that her upper lip stuck to her front teeth and stayed glued there all the while she tried to speak of her million-dollar listing’s amenities. She recalls, “I kept talking, hoping to hear someone holler “cut” like they had for Diane. But no, they just let me ramble on, looking like a fool.”

Although not a social climber or a name dropper, Sue has had a way of crossing paths with celebrities. She was vacationing in Maui, strolling along the beach, when she met a man walking toward her. She smiled and said, “Has anyone ever told you that you look a lot like Chevy Chase?” He looked, paused, and replied, “Yes, I am Chevy Chase. Nice to meet you.” Through Sue, our family has gotten to know golfer Tom Weiskopf (who flew my dad from Arizona to Minneapolis on his private jet), baseball player and manager Dusty Baker (who would give Sue and Dad dugout tours when they came to his spring training baseball games), Kansas City Chiefs football owner Lamar Hunt (who invited our family to his owner’s box to watch a Chiefs vs. Denver Broncos game), and singer/songwriter Willie Nelson. Of all these occasions, the most memorable is our evening with Willie.

Annie D’Angelo met Willie Nelson while she was working as a makeup artist on the set of the 1986 television remake of the film Stagecoach. In addition to Willie, the movie starred Kris Kristofferson and Johnny Cash. Annie and Willie were married in 1991. Sue had become friends with Annie years earlier when they worked together at a restaurant in Long Beach. She was among Annie’s close group of friends who would be invited to Willie’s concerts (at the Hollywood Bowl and other nearby venues) and welcomed to visit with Willie on his bus after the performances. She was among about seventy-five of Willie and Annie’s friends invited to attend a private, surprise 50th birthday bash that Willie threw for Annie. In the summer of 2004, Willie Nelson and Bob Dylan embarked on a minor league baseball park concert tour. It was so successful that they decided to do another one in 2005. One of their stops, on July 12, would be at Midway Stadium in St. Paul, the home of the St. Paul Saints. Annie not only invited Sue and their mutual friend Patti Harris to attend the concert, but she said that Sue could invite our family and that we could be onstage for Willie’s show plus meet him on his bus afterward.

Willie, Annie, and their boys, Lukas and Micah, traveled in two tour buses. One was a “business bus” for Willie; the other was for family. Sue and Patti stopped by the afternoon of the concert. There were a few hours to spend before the concert began, so Sue suggested they do some shopping at the Mall of America. She recalls, “Annie asked me to help her find a sunglasses shop because she wanted to buy a pair for Willie. She is extremely private and rarely shares that she is married to him. We found a shop, and Annie said to the salesperson, ‘I’m looking for a pair of sunglasses for my husband. Can you help?’ The woman said, ‘Sure. Can you describe him?’ Annie hesitated and proceeded to do so. Patti and I thought, Annie, just tell her he’s Willie Nelson! But no, she avoided sharing that fact in making her purchase.”

As was typical of Sue’s tendency for misadventure, she ran out of gas on the way back to Midway Stadium on busy I-94. Annie and her boys were driving on ahead in their rental car. Sue called Annie on her cell and asked for help. Annie soon arrived with a can of gasoline, hopped over a median barrier, and poured fuel into the tank. Sue could hear Lukas and Micah hollering as traffic rushed by, “Mom, get back in here! You’re going to get killed!”

Just off stage with Willie Nelson and his band — Midway Stadium St. Paul

The weather for the evening concert was perfect—clear skies, not too hot, not too cool, with a soft summer breeze blowing. The stage was set up facing the stands in front of the centerfield fence. Sue, Patti, my dad, my wife and son (Jeanine and Ben), and I stood in the wings near Dylan’s speakers and sound equipment that would be rolled out for him after Willie’s set. As I peeked around the curtain to check out the 12,000 fans waiting for the concert to begin, I thought I must be dreaming. Willie came on stage wearing his bandana, pigtails, and sweet smile, and the crowd roared when he began to sing. He was at center stage, and with him were his sons Lucas and Micah (guitar and keyboard), his sister Bobbie (piano), Mickey Raphael (harmonica), Jody Payne (guitar), and Paul English (drums). I could have reached out and touched the piano that Bobbie was playing.

After Willie’s set, we went to his family bus, where Annie introduced us to Lukas and Micah. Lukas was waiting to join Dylan onstage. (Dylan had invited him to play a few songs with his band.) He seemed nonplussed about all that was going on. Annie reminded him of Dylan’s quirkiness. “Lukas, be sure you stay in the background and don’t step out in front of Bob. You know he doesn’t take kindly to anyone upstaging him.”

“Yes, Mom,” he assured her. “I know.”

While we visited, Willie signed autographs for fans who were waiting in line to see him. Annie told us that Willie wanted to say hi and we should be patient; he would stop by. Sure enough, Willie popped into the bus and though understandably tired from his concert, graciously visited with us. Dad, who grew up on an Iowa farm, thanked Willie for all that he’d done for farmers, and they chatted about Willie’s Farm Aid concerts. We visited and took a few photos, and soon it was time to leave for Dylan’s performance.

My dad and Sue with Willie Nelson

I am a devoted Dylan fan, so I couldn’t wait for his set to begin. I wasn’t drawn to his ’60s music, but I became hooked when we attended his Rochester concert in 1997 with friends Frank and Sarah Earnest. It was the first performance of his I had seen. He came onstage with his band, and without a word of introduction played “Jokerman.” Something about the song and the way Dylan sang it captivated me. From then on, I was hooked. I have nearly all of his albums, and Jeanine and I have traveled the Midwest to see him in concert more than twenty times. Therefore, when I found out that we could be on stage with Willie for his concert, I thought, wouldn’t it be something if we could just stay there for Dylan’s set? But this was not to be. Annie said Dylan had strict orders that no one would be in the wings when he played; Bob didn’t tolerate any distractions.

We left Willie’s bus and returned to the stadium just before Dylan went onstage. Ben and I thought, because we had our backstage passes, that we might get a candid photo of him. Ben slipped under a rope that led to the area behind the stage that no one in the audience could see. In a few minutes, Dylan (wearing his trademark black suit and bolero hat) and his bodyguard appeared in an opening in the centerfield fence. There Ben and I were, alone with Dylan (all business, straight backed, and unsmiling) and his muscular bodyguard, who looked as serious as Bob. Dylan glanced to his right when he heard Ben snap a few photos. In a heartbeat, the bodyguard approached Ben, demanded he delete the photos he had just taken, and watched to be sure he did so. As we left, Bob walked onstage to thousands of screaming fans, and we heard the loudspeaker announcer saying, “Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome Columbia Recording artist Bob Dylan!” Bob started with “Drifter’s Escape” and sang nonstop through his “Like a Rolling Stone” encore. Willie had to be on the road again right after the show, so he couldn’t use the hotel suite that had been reserved for him and his family. We accepted his offer to stay there that night.

My family still talks of the magical evening with Willie and Bob. And to think that that experience, plus so many other memorable ones we have had with Sue, would never have happened had she died that November night a half century ago.

For more about me and my writing, see www.mransomwriter.com